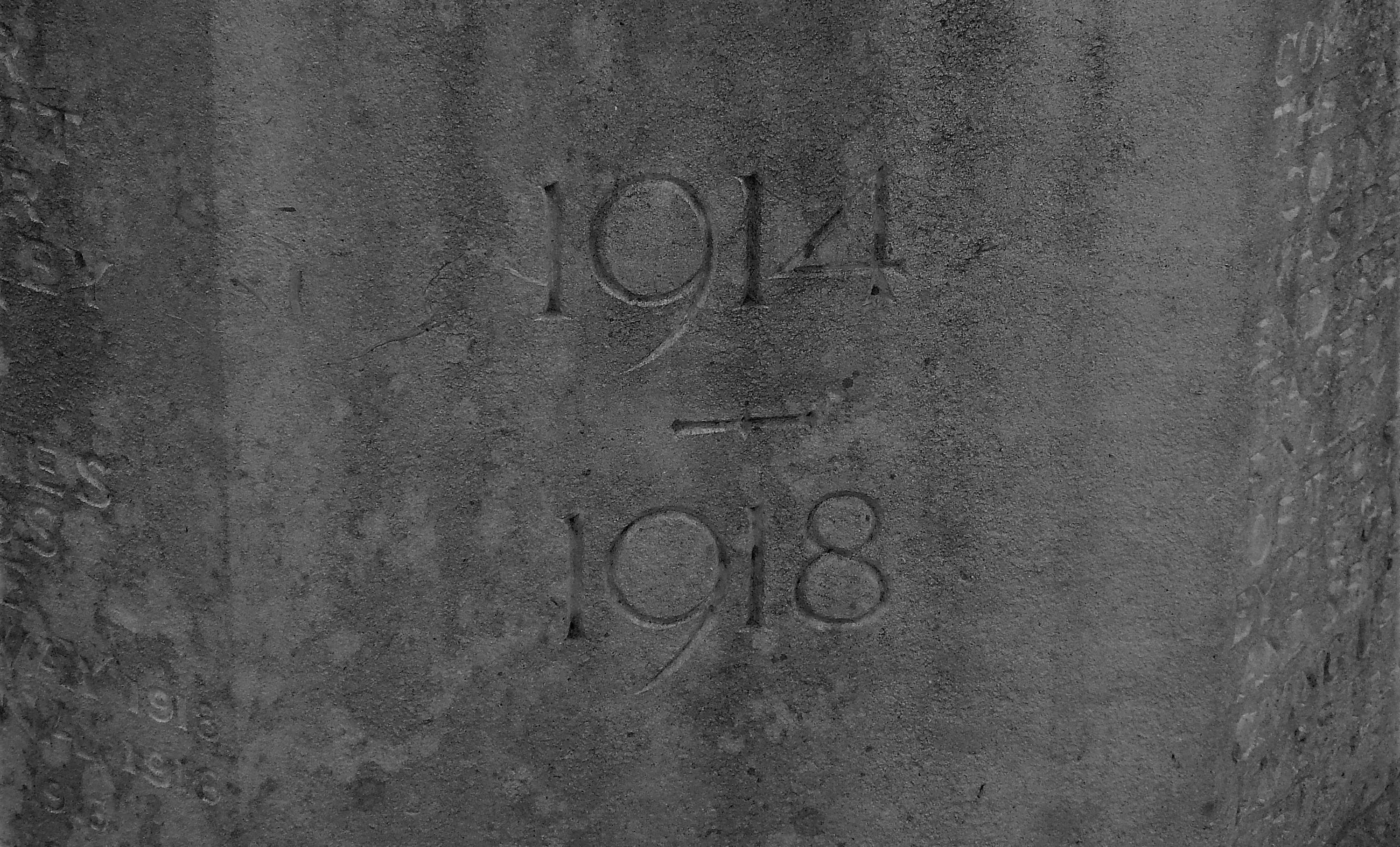

I don’t think Carl Sandburg (1878–1967) is as widely read in the UK as he has been in his native United States. Perhaps his declamatory, free verse style is more of an American taste. I had never even heard of him when I saw this poem displayed in a tube train carriage as part of the Poems on the Underground initiative some years ago. I think it was published in 1918.

What brought it back into my mind more recently? I think it must have been an article about the Ukraine war that I read not long ago, illustrated with a photograph of a trench that could have come from the first world war.

Nothing changes, I thought and that is the message of this poem. War seems to be a permanent part of the human condition. People forget. They don’t like to think about it, so nothing changes. The personification of the grass in this straightforward and direct poem represents the process of forgetting.

Grass by Carl Sandburg

Pile the bodies high at Austerlitz and Waterloo.

Shovel them under and let me work—

I am the grass; I cover all.

And pile them high at Gettysburg

And pile them high at Ypres and Verdun.

Shovel them under and let me work.

Two years, ten years, and passengers ask the conductor:

What place is this?

Where are we now?

I am the grass.

Let me work.